“On Background” is a series of blog posts wherein I talk about the books, films, and other media that would come to inform me in writing WE TAKE CARE OF OUR OWN. My gratitude to the authors, journalists, filmmakers, and thinkers responsible for these works is hereby assumed.

I can’t remember where I first saw it—it may have been in an essay about Margaret Atwood, or maybe it was an essay by Margaret Atwood—but somebody’s advice for writing dystopian literature goes like this: Take something happening to a small minority and have it happen to the whole world.

I love that definition, not only because it distills the mechanics of an entire genre in one soundbite but because it also showcases the utility of the genre–a big reason why stories exist is to provide insight through empathy, and so enlarging a problem until it affects everyone strikes me as a very effective way to provide such insight.

But I think my novel, We Take Care of Our Own, gets it backwards, because it takes something that might be happening to all of us and has it happen to a small minority.

I’ll try and tell you what I mean. We Take Care of Our Own tells the story of a government-sponsored program wherein psychologists talk veterans diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder into channeling their most violent impulses toward the killing of select “enemies of the state,” including journalists and anti-war activists, via mass shootings. We’re talking here about a dynamic where those in power (the government) coerce the vulnerable (PTSD-afflicted soldiers) in order to neutralize/destroy those threatening the status quo (journalists, anti-war activists). Now, I don’t consider myself any kind of conspiracy theorist—I think conspiracy theories are, at their core, fan fiction for reality—but I think it could be argued that we, all of us, are being coerced into neutralizing/destroying those who threaten the status quo (journalists, activists, artists, our personal moralities, our innate sense of logic) every day, right now.

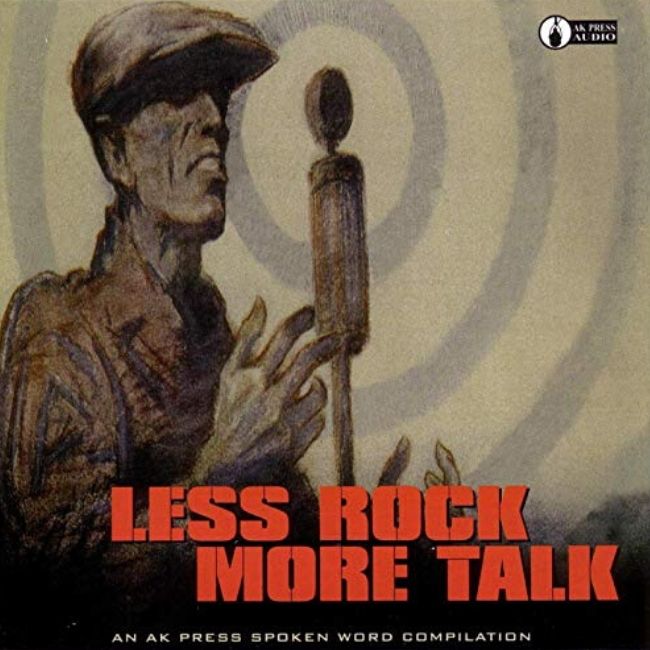

One of the first pieces of media to get me thinking about these types of things (secret government programs, psychology, power, coercion) was a 1996 CD that I checked out from the Nashville Public Library, Less Rock More Talk. It’s a sampler of various writers’ and artists’ takes on stuff like the role of the government, the military-industrial complex, income inequality, et cetera. Every one of its 11 tracks is worth listening to at least once, regardless of your personal politics, but my favorite track is a Jello Biafra speech titled “Gotta Be Ready,” where the former Dead Kennedys singer encourages what sounds like a decent-sized Bay Area crowd to consider what they might do were the reins of power to fall suddenly into their laps:

In some situation I hear about right now, what would I do? What am I good at? What can I do best? What would I most like to be doing that’s different from the rest? It’s an ongoing exercise that takes years of bouncing stuff like this around in your head when you feel like it, putting it back on the shelf when you don’t… just so long as you use it, develop it, keep getting better at it, because, like in any contact sport, in crisis mode brain wrestling, practice makes perfect.

Biafra then pivots to the need for people to unify before they can challenge the status quo, and how the difficulty of unifying is exactly what those in power are counting on to hold on to power. That’s when he gets off a line that had me rewinding (or whatever one used to do to make CDs go back a few seconds) again and again:

Divide! Divide! Divide! Let the unified few keep the quarreling majority from sharing in what is rightfully everyone’s!

It was another couple of years before I came up with the idea for We Take Care of Our Own, and there would be many, many other texts, films, recordings, and conversations to be experienced before I could develop the idea to my own satisfaction. But it’s possible that one line was the spark that, unbeknownst to me, would one day lead me to say, “Hold on… secret government program. Yeah. That could work.”

Later on I would discover that one of the nifty things about having an idea about a “secret government program” is that there’s always a real-life precedent: at some point over the last 100 or so years, the U.S. government likely did try some version of your idea, often on people they deemed disposable (minorities, low-ranked soldiers, the mentally impaired). At the same time, most of the details around any secret government program have remained secret, and this enables the writer to have fun filling in all those details.

While there’s no real-life precedent for a secret government program that turns PTSD-afflicted veterans into mass shooters, Project MKULTRA, the CIA’s decades-long attempt to develop an effective technique for coercion and brainwashing, served as inspiration.

By the way, “crisis mode brain wrestling” is another very good definition of dystopian literature.